Two Carbon Co-Conspirators Need to Be Stopped to Tackle Climate Change

Cutting CO2 and methane simultaneously helps meet global temperature targets faster. This requires setting both short- and long-term metrics going forward.

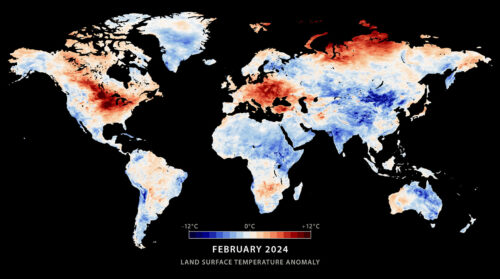

Scientists now expect Earth’s temperature to surpass the agreed upon 1.5ºC safety threshold as soon as 2027. Climate change is no longer a problem for future generations. It is our crisis to manage — now. As the planet heats up, climate change is increasingly unleashing superstorms, historic floods, wildfires, relentless heat, and infectious diseases. The next five years is a critical timeframe when it will likely be determined when, by how much, and for how long Earth overshoots the 1.5ºC guardrail. When there is no time to waste, there are actions we can already take now to put the odds in our favor. We can begin by looking at the two biggest drivers of warming — methane and carbon dioxide — and seeking dual metrics and separate targets.

Two carbon compounds are driving climate change

The word “carbon” — think carbon emissions, carbon pricing, Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism –— has become synonymous with the climate pollutant carbon dioxide (CO2). But other carbon compounds are also responsible for the rapidly changing climate. Another prime culprit is methane (CH4). According to the IPCC, methane contributes 0.5ºC to current warming, second only to carbon dioxide’s contribution of 0.8ºC. These two threats to climate security — CH4 and CO2 — largely determine how fast warming will occur and how warm Earth will get in this decisive decade.

Carbon dioxide’s climate contribution is simple but very damaging. Once it is emitted, CO2 remains intact in the atmosphere, trapping heat for centuries.

By comparison, methane’s chemical journey is complicated, driving climate damage every step along the way. Methane is deemed a climate “super pollutant” given its powerful, near-term warming effect on the planet. If we equate carbon dioxide’s warming effect to one blanket wrapped around the Earth, methane – over its ten-to-twelve-year lifetime – wraps more than 80 blankets around the planet. Moreover, some methane reacts to form ground-level ozone, which pollutes the air while also warming Earth. Ultimately, methane in the atmosphere reacts to form carbon dioxide, adding to the single blanket around Earth.

Separate and simultaneous mitigation of these two major climate pollutants is required. This means moving away from a single metric that compares their emissions on a 100-year timeframe to a “multi-basket” approach. After all, if methane is graded on a 100-year warming scale, its effect is largely masked compared to CO2. Methane’s short-term warming potential cannot be overlooked as countries around the globe work to meet near-term climate targets, and it stands as one of the biggest opportunities to achieve them. According to a recent study of mitigation on preserving Arctic summer sea ice, “fast action to cut methane … combined with net zero carbon dioxide by 2050 goals could yield an 80 percent chance of success by end of century (as opposed to 50% chance without methane action).”

Fast action to cut methane … combined with net zero carbon dioxide by 2050 goals could yield an 80 percent chance of success by end of century (as opposed to 50% chance without methane action).

Living in a warming greenhouse with rising emissions

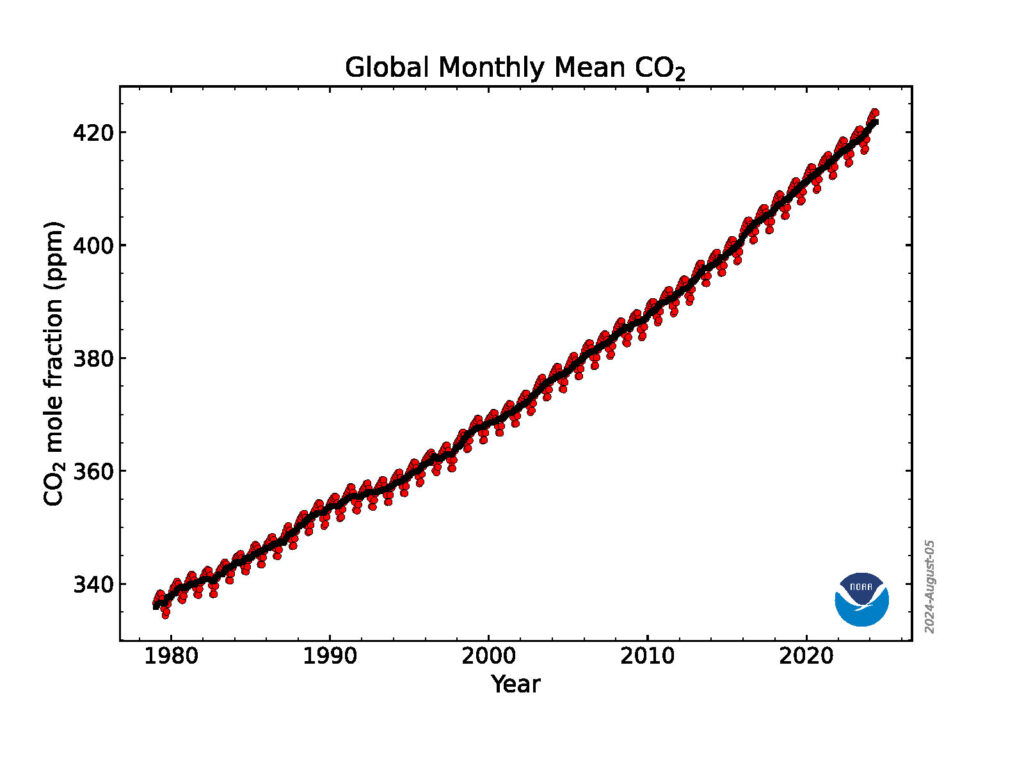

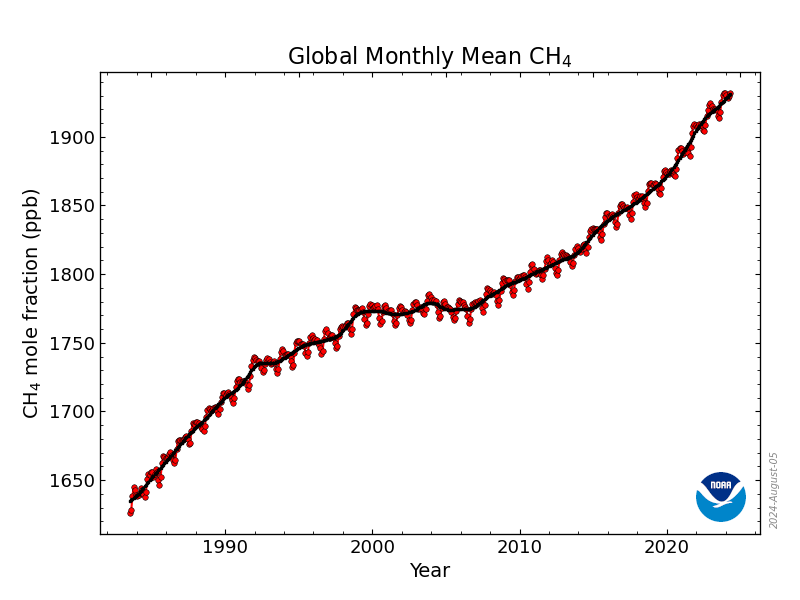

Earth’s capacity to trap greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) is vast, leading to hotter, more acidic oceans and higher global temperatures. Atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide and methane have been rising in recent decades and scientists are plotting their course, as shown in Exhibits 1a and 1b.

Exhibit 1a (top): Increase in global monthly mean concentrations of atmospheric CO2

Exhibit 1b (bottom): Increase in global monthly mean concentrations of atmospheric methane

Source: NOAA, https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/ Accessed July 1, 2024.

Human civilizations developed over the last 6000 years when global temperatures and CO2 levels were relatively stable. In 1989, the safety threshold drawn by scientists at 350 parts per million (ppm) CO2 concentration in the atmosphere was breached after decades of industrialization spurred the burning of oil, gas, and coal and shifted land use. And CO2 levels continue to rise. As of June 2024, CO2 concentrations rose to record levels of 427 ppm, a 54-percent increase since pre-industrial times.

Atmospheric methane concentrations have risen even faster than CO2. As of April 2024, methane concentrations nearly tripled since pre-industrial times to 1932 parts per billion (ppb). Moreover, some of the largest-ever double-digit increases of 10-18 ppb annually occurred since 2020.

Durable climate action to lessen risks and reduce the ongoing toll requires us to do two things at once: steadily reduce carbon dioxide emissions and immediately mitigate methane emissions.

Adopting new climate metrics to drive climate action

Climate action has prioritized CO2 mitigation over the past three decades. At the first climate conference (COP1) in Berlin in April 1995, the United Nations recorded 200 documents outlining the steps required to address climate change. Ten of those documents detailed carbon dioxide; zero referenced methane. At COP2 in Geneva, the decision to account for emissions over a 100-year timeframe was cemented and then reinforced at COP21 in 2015.

Looking out 100 years to 2100 and focusing mostly on CO2 was likely more a political decision than a scientific one, disregarding early 1970s scientific evidence that methane was as important as carbon dioxide in forcing warming. It took 40 years and fracking taking off in the United States for methane – present in oil reservoirs and a main component of gas – to finally be recognized as a potent yet preventable climate hazard.

Still, emissions accounting has retained the arbitrary 100-year timeframe established at COP2 that massively understates methane’s contribution to climate change. This is done using a single carbon dioxide-equivalent (CO2e) metric known as the Global Warming Potential (GWP), which combines different GHGs’ climate-forcing abilities. As the importance of both near-term and longer-term warming gains salience, there have been increasing calls for separate reporting of short- and long-lived climate pollutants. Research finds that combining gases with short- and long-lived emissions into CO2-equivalents using GWPs leads to ambiguity that “obscures the distinct warming impacts” of each pollutant. Other studies find there are immediate and long-term benefits from simultaneous progress on CO2 and methane mitigation. As such, experts point to the benefit of adopting two separate targets, one for methane with near-term goals and the other for CO2 with long-term goals.

Since the GWP was introduced in 1990, there has been active debate around climate metrics, with the IPCC noting that the metric choice be determined by individual decision makers and thereby made a political one. The choice of the time horizon depends in part upon whether a stakeholder emphasizes shorter-term processes, such as temperature change or speed of climate change, versus the focus on longer-term phenomena, such as sea level rise or the eventual magnitude in climate change.

In reality, however, both shorter and longer time frames are critical to minimize real-world climate risks. This involves uniformly mandating countries to set nationally determined contributions (NDCs) for methane alongside carbon dioxide. It also underscores the need to routinely report dual metrics, including the more immediately actionable 20-year metric (GWP20) alongside the 100-year metric (GWP100). And at COP28 in the Global Stocktake, countries were encouraged to report economy-wide NDCs and include all GHGs.

Addressing warming in this decisive decade

Adopting dual metrics is not novel. When investing, we use stocks for short-term gains and bonds for long-term gains to balance financial risks. When our blood is drawn, more than one metric is assessed to deem us “healthy.” And US policymakers successfully battled back acid rain by setting two different standards, one for sulfur dioxide and another for nitrogen oxides.

The goal is to establish a near-term methane-specific emissions budget that is “analogous and complementary” to the current carbon dioxide budget. Slashing both CO2 and methane simultaneously can get us closer to critical climate targets faster, as shown in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2: Avoided warming from simultaneous mitigation of CO2 PLUS methane compared to a CO2-only pathway

Source: Authors’ plot using modeled data from Reisinger, “Why addressing methane emissions is a non-negotiable part of effective climate policy”

Time for urgent call to action

The competing prioritization of CO2 and methane is a false narrative that exacerbates the climate emergency we are experiencing today. Instead, strategies targeting CO2 and methane are complementary and not interchangeable.

Adopting a dual metric for methane mitigation, one consistent with the Global Methane Pledge that calls for a 30 percent reduction below 2020 levels by 2030, is expected to reduce climate overshoot by a factor of seven compared with the current single metric for CO2 reductions. Looking to mid-century, this calls for a 43 percent reduction in methane emissions by 2040 and 50 percent reduction by 2050 on top of any net additional methane emissions from climate feedback from natural sources.

A growing constellation of public, private, nonprofit, and joint venture satellites and other instruments are available to spot outsized methane and carbon dioxide emissions. These measurements, along with advanced models, enable more accurate GHG accounting and reporting. Studies agree that methane emission intensity performance standards below 0.2 percent is feasible and necessary from the oil and gas sector. And other sources of methane are relatively easy to spot and stop, including marginal and orphaned wells that can leak as much methane as they produce, underground coal mines, and landfills with decomposing organic waste.

Simultaneously slashing methane and cutting carbon dioxide is entirely doable in this decisive decade. Dual metrics that measure, monitor, report, and verify these major short- and long-lived climate pollutants are needed to maintain the health and security of people and the planet.