Black Family Single Mother, Son and Daughter Hugging and Smile in the City. Loving Mom, Boy and Girl Together Feels Fun. Carefree Weekend Concept

We Can End Energy Poverty in the Electric Sector: Here’s How

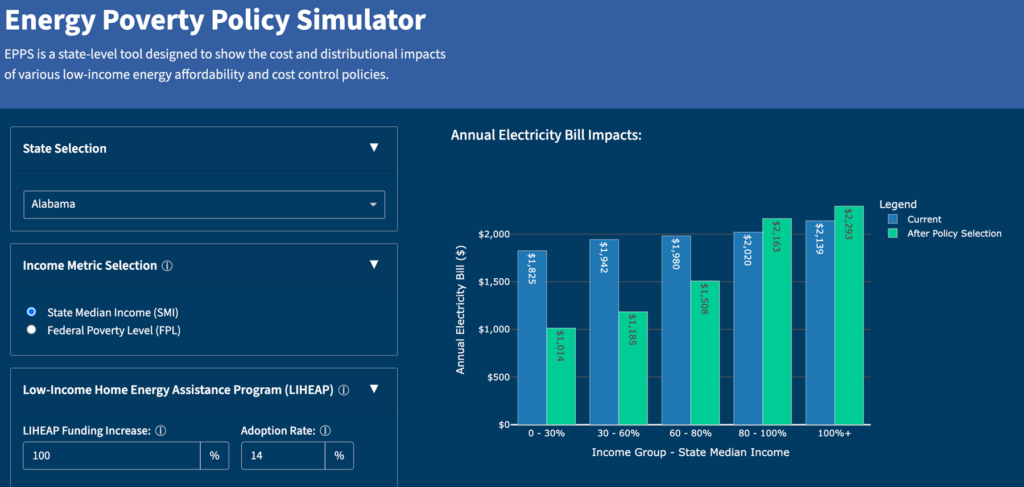

RMI's Energy Poverty Policy Simulator can help lawmakers, regulators, and energy sector stakeholders chart a path to end energy poverty.

Highlights

- One in three US households reported forgoing necessities, such as food or medicine, to pay household energy bills.

- Across the United States, electricity customer debt totaled $21.1 billion as of September 2024.

- RMI’s new Energy Poverty Policy Simulator (EPPS) tool allows regulators, advocates, and other stakeholders to model the benefits and costs of varying policies to reduce energy poverty.

- EPPS found that ending energy poverty could cost as little as $9.3 billion nationwide, just over one-tenth of 1 percent of annual federal spending.

Average US electricity rates rose 4.8 percent per year from 2019 to 2023, outpacing inflation. As energy costs continue to rise, millions of Americans are falling into energy poverty — struggling to afford the energy necessary for basic needs such as heating, cooling, and cooking.

This financial strain often forces difficult decisions. Families may cut back on food, delay medical care, or keep their homes at unsafe temperatures in order to cover utility bills. The burden is often heavier for those living in poorly insulated or inefficient housing, where energy use is harder to control.

For many households, this struggle follows a predictable and punishing cycle. It begins with a missed payment. That first missed payment in turn leads to growing debt, which, if left unresolved, results in disconnection notices that threaten a household’s stability. To stave off shutoffs, customers may take on risky, high-cost loans or seek emergency aid — only to find themselves back in the same precarious financial position the next month. The cycle repeats, locking families in a state of persistent energy poverty.

However, we have a solution. RMI’s new Energy Poverty Policy Simulator (EPPS) tool allows regulators, advocates, and other stakeholders to model the benefits and costs of different energy poverty policies in their state. RMI analysis based on the EPPS found that ending energy poverty could cost as little as $9.3 billion nationwide.

Energy poverty by the numbers

In 2024, one in three US households reported forgoing necessary expenditures, such as for food or medicine, to pay their household energy bills. This is not distributed evenly across demographic groups. Black and Hispanic households are more likely to be energy insecure than white households, even when accounting for leading factors of energy insecurity including housing condition and energy burden.

When customers can’t afford their bills, they fall behind — often quickly. As of September 2024, customer debt (or “arrears”) has risen to $21.1 billion with over 21 million households (16.3 percent of all households) owing $15.4 billion to electric utilities and 15.1 million households owing $5.6 billion to natural gas companies.

Customers in arrears may resort to taking out risky loans, such as payday loans, to pay their past-due bills and avoid disconnection. Payday loans carry an average annual interest rate of 400 percent), exacerbating cost pressures and further entrenching customers in the cycle of energy poverty.

When customers are unable to pay down their arrears, they risk losing service altogether. While comprehensive national shutoff data is unavailable due to insufficient disconnection data reporting policies, experts estimate that there are between nearly three million and six million disconnections in the United States annually.

Of households that received a disconnect or delivery stop notice in 2020, 27 percent were Black, which is disproportionately high compared to the share of the US population that is Black. Similarly, Latino households are disproportionately more likely to face electricity service disconnection, with available data showing that between 2019 and 2020 they were 2.4 times more likely than white households to be disconnected sometime in the past year.

It doesn’t have to be this way. This is where the Energy Poverty Policy Simulator (EPPS) tool comes into play.

The policy opportunity to address energy poverty

Despite the magnitude of the problem, there are clear, proven policy solutions. State public utility commissions (PUCs) have the power to implement safeguard policies that help energy insecure customers afford their bills. These include the following:

- Percentage-of-income payment plans (PIPPs) — At least nine states have a PIPP program, which caps energy bills at a specified percentage of household income for income-eligible customers — ensuring that customer bills never exceed a specified affordability threshold (e.g., 4 percent of household income for electricity bills).

- Low-income discount rates — At least 14 states provide energy at a discounted rate for income-eligible customers. Like PIPPs, low-income discount rates help reduce the total size of participating customers’ bills. They can be structured as a flat discount for all eligible income groups, or a tiered discount where the discount level varies based on the income group (e.g., the lowest-income groups, or the most energy impoverished customers, receive the largest discount).

- Arrearage management plans (AMPs) — At least 10 states forgive a portion of debt for each timely payment of a new bill. These AMP programs can help customers pay down their arrearages and support them in returning to a regular payment schedule.

- Low-income energy efficiency — Most states offer targeted energy efficiency support for low–income customers to help ensure they directly benefit from improvements such as weatherization and appliance upgrades. These programs can help lower total consumption for income-eligible customers, reducing their energy bills.

Beyond these more targeted measures, PUCs can pursue cost containment policies that can reduce systemwide costs and support affordability. These include reforms to utility return on equity (ROE), economic dispatch, and clean repowering.

The cost to make all electric bills affordable: Just $9.3 Billion

The EPPS is a practical resource that enables users to evaluate how different policy portfolios perform under different design parameters, such as eligibility thresholds, funding amounts, and cost recovery models. The tool generates a series of charts illustrating how the policies affect average bills and energy burdens for both income-eligible and non-eligible customers, along with the estimated total cost of implementation.

Using EPPS, RMI modeled the costs of extending a universal PIPP that would cap electricity bills at 4 percent of household income in every state. Under the modeled scenario, all customers between 0 and 60 percent of the state median income would receive the PIPP benefit, so that their electric bills would never exceed 4 percent of their household income. This would essentially end energy poverty associated with electricity expenditures in each state, as electric bills are typically seen as affordable when they do not exceed 4 percent of a household’s income. The exact cost of this policy in each state would vary due to a number of contextual factors, but at an aggregate nationwide level would cost just $9.3 billion (see modeling assumptions at end of article for more information on our analysis).

To put that into perspective, $9.3 billion represents just 0.14 percent of the federal spending in fiscal year 2024. That’s a relatively small price to pay for lifting a major burden off millions of low-income households and creating long-term savings in health care, housing stability, and economic opportunity.

Aside from modeling the costs of ending energy poverty through a PIPP and other policy options, state policymakers, advocates, and utilities can use the EPPS to serve a number of additional use cases in their state, such as:

- Assessing how a new policy design would affect the bills of both participating and non-participating customers;

- Modeling the costs associated with extending the benefits of a specific program (e.g., a low-income discount rate) to another income group; and

- Understanding how mixing and matching various funding sources might support cost recovery for specific policies.

The EPPS can help policymakers and stakeholders bring the receipts — providing clear, data-driven evidence for the design and implementation of safeguard policies to address energy poverty.

For any questions or to request a live demo, please reach out to Maria Castillo (mcastillo@rmi.org).

Modeling assumptions

The 4 percent assumption is based on a total combined energy burden of 6 percent, which is a common threshold that states use in defining affordability. The 6 percent energy burden threshold is derived from the idea that housing is affordable when it costs no more than 30 percent of a household’s income, and that up to 20 percent of housing costs can reasonably go toward energy. Of that 6 percent, electricity typically makes up the majority of household costs — about 4 percent — with the remaining 2 percent for gas and other fuel types.

Under our analysis, the PIPP would be extended to all customers with an electricity burden above 4 percent — a condition that, in practice, applies only to households within 0 to 60 percent of the state median income. We refer to this as a “universal PIPP” because it would ensure that all customers are kept below a 4 percent energy burden.

This analysis takes into account the estimated savings from this policy in terms of avoided arrearages. Under the model, the total cost of the PIPP across states would cost $19.3 billion, but would create $10 billion in savings from avoided arrearages, for a net cost of $9.3 billion.