Scaling Low-Income Solar with the Inflation Reduction Act

Executive Summary

Tax-exempt entities can accelerate the adoption of solar photovoltaics (PV) among low-to-moderate income (LMI) communities. Leveraging the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), these organizations can take on the role of a third-party owner. This paper is intended to provide a primer on this model to interested tax-exempt entities, which might include community development financial institutions (CDFIs), green banks, electric cooperatives, 501(c)(3) organizations, and others.

This paper is divided into the following sections:

- Introduction

- The Opportunity for a New Kind of Third-Party Ownership

- Challenges and the Means to Address Them

- Early Adopters

- Possible Model Enhancements and Capital Sources

Introduction

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) represents an unprecedented level of investment by the federal government to accelerate equitable clean technology deployment. Most notably, all three components of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) — the National Clean Investment Fund (NCIF), the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator (CCIA), and Solar for All (SfA) — are oriented toward supporting disadvantaged communities; in fact, CCIA and SfA are designed to focus exclusively on low income and disadvantaged communities. In addition, the IRA created new bonus credits to further incentivize clean energy deployment in low-income and Tribal communities.

The federal government’s particular attention to low-income and disadvantaged communities is warranted as, to date, these groups have not benefited proportionally from the clean energy transition. In 2022, the median income of rooftop solar adopters was almost twice that of the broader population, and studies in California have found “persistently lower levels of PV adoption in disadvantaged communities.” Given the ability of rooftop solar to reduce energy costs for consumers, this represents a missed opportunity to mitigate low-to-moderate income (LMI) household energy burden, or the percent of household income that goes toward energy costs. The energy burden for LMI households is estimated at 8.6% nationally, roughly three times the energy burden for non-LMI households.

There are three principal financial barriers to LMI solar adoption: high up-front costs, lack of accessible and affordable financing from trusted sources, and the design of federal clean energy tax incentives. The GGRF program was designed to provide resources to address the first two challenges; the structure of federal clean energy tax credits remains a significant barrier to LMI clean energy adoption, however.

Low-income households face three key disadvantages in fully utilizing federal tax incentives:

- Insufficient Tax Liability to Monetize Credits: Tax credits are used to lower a taxpayer’s annual tax burden. Individuals who purchase a solar energy system or standalone storage system for their home are eligible for the Section 25D Residential Clean Energy Credit that allows them to claim 30% of the cost of system as a credit against any taxes that they owe. LMI households at times do not have a sufficient tax liability to offset with credits, meaning that they are unable to fully monetize the clean energy credits themselves. RMI analysis found that, due to this challenge, 4 out of 10 US households would not receive any benefit from the residential solar tax credits, and 3 out of 10 would be able to receive only a portion of the full benefit in the first year.[1]

- Ineligibility for Alternative Monetization Mechanisms: While individuals who own solar PV systems are only able to monetize the 30% Residential Clean Energy Credit (Section 25D) by applying it against their own tax burden, this is not the case for other types of owners. In contrast, commercial and tax-exempt entities are eligible for solar incentives contained in Sections 45 and 48 of the tax code (such as the investment tax credit [ITC] and production tax credit [PTC]), and as a result have access to new monetization mechanisms created by the IRA. Specifically, tax-exempt organizations such as nonprofits and local governments can receive ITC and PTC credits as a direct cash payment (known as elective pay or direct pay). Meanwhile, commercial entities are able to sell the credits to others through a mechanism known as transferability.

- Inability to Access Bonus Adders: In addition to extending the availability of clean energy investment incentives for businesses and tax-exempt organizations (Section 48 and its successor, Section 48E) through at least 2032, the IRA also added bonus credits (“adders”) to incentivize projects that meet various criteria. For example, if a particular project satisfies prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements (as applicable), uses specified amounts of domestic materials, is located in an “energy community,” and is eligible for the ITC (Section 48), the owner could claim a tax credit for 50% of eligible costs. Furthermore, projects that are located in or sufficiently benefit low-income households may be able to increase the value of their ITC credit by another 10%–20% of eligible project costs. These adders are not available to individual taxpayers through the Section 25D federal residential solar energy credit, which is limited to 30% for projects placed in service before January 1, 2033.

In some jurisdictions, low-income households can manage these challenges by using existing third-party ownership models, such as leases or power purchase agreements (PPAs) offered by for-profit solar developers, but these approaches are not without their own drawbacks. In a for-profit, third-party structure, a rooftop solar developer owns the system and bills the household monthly; the developer monetizes the commercial tax credits and passes some portion of the benefit on to households in the form of lower monthly energy payments. These traditional third-party structures typically provide less attractive long-term financial returns to home owners than owning the system directly. Moreover, while third-party models appear to have successfully increased LMI household adoption, they are becoming less common, due to limiting regulations in some states and a national shift within the solar industry away from third-party structures.

All the above suggests a need for a new LMI solar financing model that fully leverages the various forms of funding, financing, and tax incentives provided by the IRA. This paper explores a newly possible financing mechanism in which tax-exempt entities take on the role of third-party owners, combining GGRF capital, direct pay of applicable tax credits, and the enhanced commercial ITC incentives to significantly enhance the potential for LMI rooftop solar adoption.

The Opportunity for a New Kind of Third-Party Ownership

Financial Model Overview

The IRA included provisions for several new programs and mechanisms that, when combined, create a compelling opportunity for tax-exempt financial entities to act as third-party owners of solar assets. The proposed model brings together the following IRA programs and innovations:

- Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF): The GGRF’s three funding programs will collectively provide nearly $27 billion to a variety of recipients, in particular non-taxable financing entities such as community development financial institutions (CDFIs),[2] certain green banks,[3] and national nonprofits. GGRF funds offer an important opportunity to capitalize the envisioned solar projects at scale.

- Elective Pay: Prior to the IRA, there was no means for tax-exempt organizations (e.g., states, local and Tribal governments, municipal or cooperative utilities, nonprofit institutions) to directly leverage federal clean energy tax credits as an owner. The only means these organizations had of leveraging tax credits was to partner with for-profit intermediaries that would, typically, leverage complex — and costly — project ownership structures to monetize the available tax credits. With the new elective pay (often referred to as “direct pay”) mechanism, tax-exempt institutions now have the ability to receive cash payments from the US Treasury for certain tax credits, including the ITC and PTC.

- PTC and ITC Adders: The PTC and ITC tax credits in sections 45 and 48 of the tax code include a variety of potential bonus adders that can be leveraged if the necessary criteria are met — in the case of the ITC, the adders can enhance the value of the credit to as much as 70% of eligible project costs. Specific adders available include: a 10% adder if a sufficient percent of materials is domestically sourced (often referred to as domestic content); a 10% adder for projects located in energy communities; and a 10%–20% bonus credit for projects that are located in or provide sufficient benefit to LMI communities (ITC only).

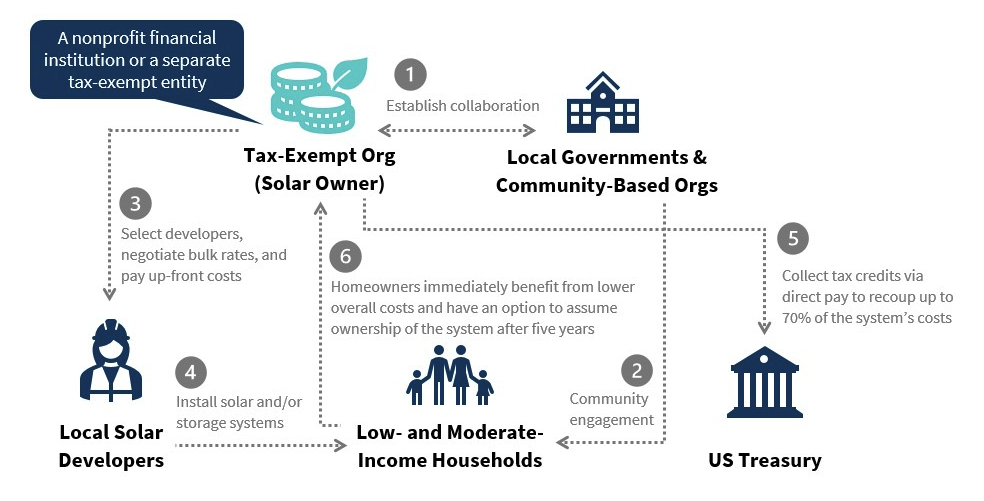

Together, these programs and mechanisms create the opportunity for tax-exempt financial institutions to help LMI households take advantage of the ITC and benefit from the more generous commercial clean energy incentives. This could be achieved through the steps illustrated in Exhibit 1.

Possible Implementation Steps

- Establish collaboration: A tax-exempt organization interested in acting as a third-party owner engages local partners (e.g., city governments, community-based organizations [CBOs]) to establish a collaboration and shared set of objectives.

- Engage Communities: Local partners engage the local community to conduct needs assessments, structure an offering, and identify interested households.

- Select Developers: The tax-exempt entity and local partners conduct a solicitation to identify local contractors and negotiate terms.

- Install Projects: The solar contractors work with identified households to assess rooftop potential, provide design options, secure the necessary permits, and ultimately install — and possibly maintain — the solar assets.

- ITC Direct Pay: In the one to two years following the system installation, the tax-exempt owner of the system collects the ITC payment directly from the US Treasury in cash.[4] To avoid “recapture” of the tax credit by the government, ownership must remain unchanged for five years.

- Homeowner Savings and Ownership: Homeowners make regular lease payments to the tax-exempt entity, and benefit from immediate savings.

Model Benefits

This financing and ownership structure provides a solution to the three disadvantages low-income solar households face to fully utilizing federal tax incentives identified in the introduction. By shifting the ownership of the system to a tax-exempt entity with an opportunity to leverage direct pay, this model eliminates the need for homeowners to have sufficient tax-appetite to utilize the credits. This shift also provides a means for projects to directly benefit from the various ITC and PTC adders, particularly the low-income community bonus credits that are available for up to 1.8 gigawatts of projects per year of ITC projects that provide sufficient economic benefit to LIDAC and Tribal communities. Indeed, the fact that the owner of the project is a tax-exempt entity also increases the odds of accessing the low-income bonus adder, as 50% of the 1.8 gigawatt allocation is reserved for projects meeting certain additional selection criteria that include ownership by 501(c)(3) and other tax-exempt organizations.[5]

As a result, this model generally offers substantial financial benefits compared with standard solar loans or traditional leases as offered in the market today. To illustrate this, consider the example of a low-income household in southern Nevada that pays no federal income tax and, as a result, receives no benefit from the residential clean energy credit. According to According to RMI’s Green Upgrade Calculator, a rooftop solar system owned by the individual taxpayer and financed via a loan might provide a household cost savings of $10,000 over the course of 20 years in the absence of monetizing any federal incentives. A solar lease leveraging the ITC through direct pay at the 30% or 60% level could, instead, provide cost savings between $12,600 to $17,800 over that same period.[6] Moreover, these estimates are likely underselling the potential, as they assume that tax-exempt owners would require returns comparable to those sought by private solar developers, and therefore price the lease at only a moderate discount or at no discount from the market rate. RMI research suggests that mission-driven local lenders, such as CDFIs, CBOs, or nonprofit green banks, supported by the influx of GGRF capital, could offer financial products with lower return requirements. Reducing the required rate of return from 12% to 8% on the aforementioned solar leases further enhances the modeled savings in our example from $16,300 (30% ITC) to $20,400 (60% ITC).

The Tradeoffs Between Direct Ownership and Returns. One potential critique of this model is that it does not guarantee ownership of the asset by the beneficiaries (i.e., low-income households). While households can be given the opportunity to purchase the system after the necessary five-year holding period, many may not have the necessary capital to do so, and others may prefer to continue to have a third-party entity own and maintain the system. As such, ownership by beneficiaries should be weighed against the financial benefits that this model can provide.

Potential Owners

An inexhaustive list of potential tax-exempt entities that could serve as solar asset owners include:

- CDFIs: Tax-exempt CDFIs could leverage their local community relationships and GGRF funding to support this model as a means to further their objectives of fostering economic opportunity. Many CDFIs have strong connections to local communities, enabling them to secure buy-in from community members and provide attractive financial terms that more accurately reflect a household’s ability to pay (e.g., by considering factors beyond FICO scores such as utility bill repayment history). Moreover, CDFIs could leverage capital flowing from the GGRF program (particularly CCIA) to help capitalize projects. That said, CDFIs need to be cognizant of certain compliance requirements that would impact how this model is deployed; these considerations are discussed further in the next section.

- Nonprofit Green Banks: State and local nonprofit green banks in the United States are purpose-driven institutions with missions to catalyze investment in climate and environmental solutions. They may be private, public, or quasi-public institutions, and they are usually capitalized with limited public funding that they use to attract multiples of private investment. In order to achieve their missions, green banks develop specialized expertise in decarbonization projects and financial products that increase project bankability and decrease risk. As a result, nonprofit state and local green banks may be in a position to supply tens of millions of dollars to scale up this model relatively quickly.[7]

- Co-ops: Rural electric cooperatives (co-ops) are nonprofit, member-owned utilities that provide power to 42 million people across nearly every state. Their experience managing grid infrastructure and existing utility-member relationships with households position them well to pursue this model. Even before the IRA, co-ops had introduced a diverse set of programs intended to remove barriers for member uptake of energy efficiency, rooftop solar, and other distributed technologies. Programs that tie utility investment to the meter and collect repayment through the existing electricity tariff, such as Pay As You Save®, have been particularly successful in allowing access to low-income members, renters, and other households that can be disqualified from traditional financing programs. These programs can also be designed to ensure that non-participants do not unduly subsidize participants. Finally, co-ops can capture the grid benefits of distributed solar installations for their entire systems.

- Local Governments: City and county governments with ambitious clean energy goals and strong energy equity focus may be well-positioned to leverage this model. Local governments may have the ability to leverage existing partnerships with community-based organizations to build support among low-income communities and recruit participants. In addition, local governments that operate their own municipal electric utility could, like co-ops, leverage their existing billing infrastructure and knowledge of the local grid to streamline billing and optimize system benefits.

- Other 501(c)(3)s: In addition to the specific nonprofit entities identified above, this model may also be of interest to other local or national nonprofit organizations with financing capabilities. This could be particularly true for organizations that support and engage with homeowners (e.g., Habitat for Humanity) or nonprofit organizations that serve and have established long-standing relationships with LIDAC communities.

- Tribal Governments and Utility Authorities: As sovereign nations, many Tribes are interested in pursuing renewable energy projects that are aligned with their energy sovereignty and environmental values. Moreover, Tribes are primarily rural and face some of the lowest electrification rates in the country, so providing solar to homes without access to electricity is an important priority in these communities. Tribal governments are eligible for direct pay and have a deep understanding of their community’s unique needs as well as the complex land ownership, jurisdictional, and permitting issues associated with solar projects on Tribal land. Tribal utility authorities that operate as tax-exempt entities may also be eligible for direct pay and would be uniquely positioned to operate solar programs by leveraging their relationships with their existing customer base.

Challenges and the Means to Address Them

Pioneers of this model have identified potential challenges that could hamper adoption by certain actors. Based on conversations with these entities and independent research, RMI has compiled the following list of challenges and potential means of addressing them.

Challenges

- CDFI Certification Compliance: Per CDFI certification guidance, CDFIs are required to have a “predominance” of their business in eligible activities — and at this time, the list of eligible activities does not include leasing. As such, CDFIs that undertake this model on balance sheet are at risk of jeopardizing their CDFI status, particularly in light of new and more stringent CDFI certification guidelines. Early movers in this space have addressed this challenge by creating distinct limited liability companies (LLCs) to house these projects, yet this adds additional legal costs and complexity to the process.

- Davis-Bacon Act: At time of publication, the EPA indicated that all projects funded by GGRF programs are subject to Davis-Bacon requirements that can impose challenges on solar contractors. Many solar contractors are not accustomed to paying prevailing wages or to the administrative burden of submitting weekly payroll records. As such, any projects that take advantage of SfA, CCIA, or NCIF funding will need to carefully select vendors and collaborate with contractors where possible to minimize the impacts of these requirements on project cost.

- Domestic Content: While utilizing domestically sourced materials may increase the ITC by 10 percentage points (the bonus adder), domestic content requirements also present a potential risk for direct pay projects — particularly if those projects might be aggregated together for tax purposes. If a project (or aggregated group of projects) using direct pay is 1 MW or larger in size, does not meet domestic content requirements, and is started after 2024, the base ITC percentage available would be reduced at a progressive rate.[8] While the initial reductions for projects starting in 2024 and 2025 are modest (90% and 85% of the 30% available, respectively), projects that initiate construction after 2025 could have their direct pay ITC eliminated completely. As such, owners should take precautions to ensure that any project or group of projects 1 MW or greater in size meets the necessary domestic content requirements.[9] Importantly, project owners should also be careful to structure their programs to avoid an undesired IRS determination that small projects need to be aggregated for tax credit eligibility purposes, potentially crossing the 1 MW or greater threshold. Currently proposed guidance from the IRS indicates that projects will be aggregated if they are owned by a single taxpayer (which includes entities filing to claim direct pay) and any two of the following conditions apply:

- The energy properties are constructed on contiguous pieces of land;

- The energy properties are described in a common power purchase, thermal energy, or other off-take agreement or agreements;

- The energy properties have a common intertie;

- The energy properties share a common substation, or thermal energy off-take point;

- The energy properties are described in one or more common environmental or other regulatory permits;

- The energy properties are constructed pursuant to a single master construction contract; or

- The construction of the energy properties is financed pursuant to the same loan agreement.[10]

- Excess Benefit: Project owners should be conscious of rules that limit the ability to stack ITC funding with restricted grants and tax-exempt debt. The “no excess benefit rule” stipulates that project owners cannot be reimbursed for more than the full cost of the project. Meanwhile, if tax-exempt bonds are part of the capital stack, the ITC payment is subject to a 15% haircut.[11]

- Liability: Project owners must be prepared to manage any underperformance, fires, or weather-related damage that might occur to the system. Although these are risks that many tax-exempt organizations are not used to bearing, managing these issues is one additional means of providing meaningful value and support to LIDAC homeowners who would otherwise have to manage these issues themselves. These risks can be limited through insurance, spreading the potential for individual system failures across larger portfolios, and housing the assets in single-member LLC subsidiaries.

- Market Education: This model is a novel financial arrangement, and early adopters have had to invest in significant outreach and education to private lenders, their attorneys, and households to generate the necessary trust and understanding to secure capital and sign contracts. A collective education campaign to private investors, community members, and other relevant actors could build confidence.

- Project Development Expertise: Many of the tax-exempt entities cited above that may reasonably contemplate such a leasing model are not traditional developers, financiers, or owners of solar projects. Learning or hiring staff with knowledge of the intricacies of the project development process may pose challenges to these types of tax-exempt entities that would require them to develop, finance, build, own and possibly operate a growing portfolio of rooftop solar systems.

- Tools and Software: The technology infrastructure needed for leasing is significantly different than for lending. For instance, to launch the Georgia BRIGHT program, Capital Good Fund had to build a customized lease-pricing tool, lease-servicing software, and APIs to push and pull data to and from installers.[12] It also had to make material changes to its intake and application forms, website landing page, and project tracking tools.

- Regulation and Legal Process: The rules and regulations around third-party ownership of solar and direct pay tax credits are substantially different from those for consumer or business lending. Early adopters have had to create new contracts between LLCs and installers, homeowners, and commercial customers; understand and comply with IRS guidance on direct pay; secure insurance policies for owned systems; and create brand-new policies and procedures for underwriting, servicing, compliance, and more. One notable issue that has arisen is the IRS requirement to make ITC payments to the ultimate owner of systems rather than individual LLCs, which has necessitated new arrangements with debt providers to guarantee the ITC payments from the US Treasury will be properly redistributed and not be subject to any parent company bankruptcy risk.

Implications

The challenges listed above highlight that, although the model is potentially powerful, its complexity may make it more suitable to organizations with the ability to defray these costs over a larger number of transactions and with knowledge of the solar development process. Smaller CDFIs and those new to clean technologies may find the risks and costs related to CDFI compliance, liability, technology, direct pay, and capitalization too difficult to navigate individually. This suggests that this model may be best suited either to entities able to spread the necessary costs across a large volume of projects, either because of their overall size or a decision to focus on this type of structure, or coalitions of smaller entities that can pool resources.

Early Adopters

There are a variety of organizations that have been exploring and implementing versions of this structure.

Georgia BRIGHT

Georgia BRIGHT is the first-ever LMI-focused solar lease program in Georgia, launched in September 2023 by Capital Good Fund (Good Fund), a Rhode Island-based nonprofit CDFI. Good Fund manages the full breadth of the process, including customer acquisition, developer solicitations, ITC bridge loans,[13] tax credit monetization, and lease payment collection. Customers typically sign up for a 25-year lease that includes operations and maintenance services such as monitoring, insurance, repairs, and battery replacement (50% of customers to date have included storage in their project). Customers may purchase the system at any time after six years by paying the outstanding balance on the project.

Impact Solar Initiative in Columbus, OH

The Columbus Region Green Fund (CRGF), a nonprofit green bank, plans to use a version of this model to run its Impact Solar Initiative, which will add 40 MW of solar to the region, create 600 local jobs, and generate $129 million in savings. Recognizing that sourcing qualified projects has been a long-standing challenge for green banks, CRGF has established partnerships with more than 50 trusted, local nonprofits and multi-family housing organizations to work with communities and create a robust project pipeline. These projects will then be housed in a new non-taxable entity, Clean Energy Ventures, which will also be responsible for conducting solicitations for contractors (who will install and maintain the systems) and signing 20-year power purchase agreements (PPAs) with multi-family and nonprofit buildings as well as six-year PPAs with single-family households. At the end of the PPA term, the solar asset ownership will be transferred to these facilities and households. To help reduce PPA costs for participants, CRGF is providing a combination of low-cost debt and a loan loss reserve (LLR) to lower the cost of private capital. Finally, CRGF intends to pair this program with a related workforce development training program (offered by a regional partner) that would provide workers for the local contractors.

Solar United Neighbors and One Roof’s Solar Lease Program in Duluth, MN

Solar United Neighbors (SUN) and One Roof, with support from the Minnesota Interfaith Power and Light, have partnered to launch a version of this model in Duluth, Minnesota. In this program, officially known as Harnessing the Power of Nonprofits to Deliver Low-Cost Solar to Low-Income Homeowners, One Roof plans to fully fund the systems using a combination of grants and tax credits, allowing them to offer the systems to low-income homeowners at no cost. The homeowner and One Roof will enter into a solar equipment lease and services agreement. This allows One Roof to maintain ownership of the system for a necessary five-year holding period, during which the homeowner will make no payments and have no responsibility for system maintenance. The solar system will be gifted to the homeowners at the end of One Roof’s ownership period. This approach is expected to save homeowners $700–$900 per year in electricity costs.

Solar4Us @ Henderson-Hopkins in Baltimore, MD

Climate Access Fund, a Baltimore-based nonprofit green bank, is using this innovative financing structure in a community solar demonstration project, Solar4Us @ Henderson-Hopkins. This approximately 804 kW system is located on the rooftop of a public contract school in a historically disinvested neighborhood and will allocate 100% of the clean electricity generation to approximately 150 LMI households. As the solar system owner, Climate Access Fund will cover up to 50% of the total system costs using clean energy tax credits via direct pay (30% base credit + up to 20% low-income communities bonus credit). Additionally, they leveraged a diverse capital stack inclusive of social impact capital, such as low-cost and no-cost debt, public and philanthropic grants, and crowdfunded debt, etc. LMI subscribers will face no up-front costs and will pay a discounted rate for their allocation of the generated electricity to Neighborhood Sun, Climate Access Fund’s local partner. Total household expense will be 20%–25% lower than their Baltimore Gas & Electric electricity costs. As a result, the Solar4Us project will enable subscribed households to save approximately $1.1 million in electricity bills over the lifetime of the project.

Public Solar NYC

New York City is also pursuing a version of this model through its Public Solar NYC program. The City intends to raise over $500 million via its municipal bond authority to create a new, stand-alone 501(c)(3) development corporation and drive $2.4 billion of solar projects. This corporation would require strong labor standards in its contractor solicitations, thereby creating high-quality green jobs, establishing apprentice programs, and providing greater opportunities for minority- and women-owned businesses.

Possible Model Enhancements and Capital Sources

The envisioned model could be enhanced further through some combination of complementary services provided by relevant parties (such as GGRF recipients) as well as partnerships to unlock additional sources of capital, economies of scale, and pooled knowledge and resources.

Complementary Services

GGRF recipients have the opportunity to both directly adopt this model and support it through a variety of means:

- Establish a Centralized Platform: One means of enhancing the potential of this model would be to establish a centralized project owner to reduce the complexity for local groups. Organizations seeking to deploy this structure will need to adopt a new role in the market (i.e., act as an owner), manage potential liability, adopt new technology to manage leases as opposed to loans, and manage the complexity of sourcing, evaluating and engaging leads for program participants, creating the necessary capital stack, securing federal tax incentives via direct pay, and potentially creating new LLCs to house the projects. Given these startup costs, which may be distinct for each state, there are opportunities to reduce overall costs by centralizing many of these functions and empowering local organizations to principally serve a deal origination and development function.

- Insure Project Owners against Liability: Residential solar projects, particularly those that include battery storage, may expose owners to liability in the event of equipment malfunction or fire. GGRF recipients could reduce the cost of insuring against these risks, and simplify the transaction process, by creating a low-cost insurance product in which project owners could easily enroll.

- Distribute Standardized Tools and Templates: An alternative means of reducing startup costs would be to create and distribute standardized templates and other tools to streamline model adoption. These may include standardized legal terminology for the leases and LLC creation, as well as standard techno-economic modeling tools to help local entities easily design systems and evaluate the financial implications of different project sizes and loan conditions for different parties.

- Provide Credit Enhancement Support: GGRF recipients can help de-risk these projects for owners by providing some form of credit enhancement support. Examples of credit enhancement mechanisms include loan loss reserve funds and subordinated debt, both of which were leveraged by the Connecticut Green Bank in their Solar Lease 2 program.

- Engage and Educate Private Financial Institutions: GGRF recipients, CDFI networks, nonprofits, green bank coalitions, installers, business associations, and others can conduct outreach to potential owners within their networks to educate them about this opportunity and provide support.

Additional Sources of Capital

To enhance and scale the impact of GGRF funds for low-income solar, nonprofit entities could look to stack direct pay with other federal policy and incentives designed to facilitate investment in low-income communities. In addition to various recurring grant opportunities (e.g., the Capital Magnet Fund), there are several programs and investment mechanisms that could help attract additional capital to leverage GGRF investments.

- New Markets Tax Credit: The NMTC is an incentive program designed to encourage private investors to finance projects in low-income communities that could complement this model. In the NMTC program, private entities agree to make an equity investment in a Community Development Entity and then receive in exchange a 39% tax credit over a seven-year period. [14] One potential means of combining the NMTC with the ITC would be to create a tax-exempt community development loan fund to house the NMTC funds and act as the owner of these projects (thereby enabling the fund to collect ITC payments via direct pay). As the NMTC awards are competitively allocated to CDE applicants, entities seeking to leverage the NMTC may wish to partner with groups experienced in navigating this program and, where possible, include a robust project pipeline in their applications. There are two potential complications regarding NMTC as an additional capital source. The first is that the credits are realized over a seven-year period, which would impose a potential further delay on beneficiaries taking ownership of the system. Another consideration is that, while the NMTC has enjoyed bipartisan support and has been extended eight times since its initial passage in 2000, the program is currently set to expire at the end of 2025.

- Community Reinvestment Act: The CRA provides a potential pathway to secure private capital for low-income solar. The CRA is a federal law that empowers supervisors to evaluate and grade commercial banks on whether they are meeting the credit needs of low-income communities where they work. Rooftop solar projects, particularly those combined with storage that enhance local resilience, have the potential to be CRA-eligible investments. However, the degree to which this type of model would be appealing to banks and the resultant opportunity for program operators to secure below-market loans are dependent on if and when a proposed set of CRA regulations are fully adopted.[15]

- Program Related Investments (PRI): In addition to private sources of capital, philanthropic and community foundations have the ability to make direct investments in opportunities using PRIs. PRIs are concessionary investments intended to further a foundation’s mission while generating below-market returns that can be re-invested. As such, large foundations interested in accelerating the adoption of clean technologies within the United States — and within low-income neighborhoods in particular — may be willing to provide capital to support this model.

Conclusion

To date, the federal government, solar industry, and nonprofit community have failed to address the persistent gap in low-income solar adoption. The combination of GGRF programs, direct pay, and IRA adders offers tax-exempt entities a powerful new means of addressing this challenge, provided they are able and willing to adopt the role of system owner and accept the associated startup costs and operational adjustments. Fortunately, interested parties have the opportunity to engage and learn from early adopters of this model, collaborate with GGRF recipients to create supportive programs that further enable this model, and engage other partners to tap into additional sources of low-cost capital.

This is a pivotal moment in the United States’ efforts to support a clean, equitable energy transition. RMI is eager to continue to engage with thought leaders and practitioners to explore and best leverage these concepts in support of that mission.

Notes

- 25D has a carryforward provision that allows taxpayers to apply the credit over multiple years.

- CDFIs are defined by the CDFI Fund as “banks, credit unions, loan funds, microloan funds, or venture capital providers” that “share a common goal of expanding economic opportunity in low-income communities by providing access to financial products and services for local residents and businesses.” See https://www.cdfifund.gov/sites/cdfi/files/documents/cdfi_infographic_v08a.pdf.

- Green banks can be public, quasi-public, or nonprofit institutions that “use innovative financing to accelerate the transition to clean energy and fight climate change.” For more information, see https://coalitionforgreencapital.com/what-is-a-green-bank/.

- The process of utilizing direct pay requires several steps, including registering the project and filing a tax return. For more guidance on this process, see Lawyers for Good Government’s Clean Energy Tax Navigator: cleanenergytaxnavigator.org.

- The reserved 50% is for entities listed in 1.48(e)-1(h)(2), which include 501(c)(3) organizations, with projects meeting the geographic criteria described in 1.48(e)-1(h)(3), namely persistent poverty counties and census tracts identified by the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool.

- Although a 70% payment is possible, RMI chose to focus on 60% here as a more realistic ceiling given some concerns around the ready availability of sufficient domestic materials to meet domestic content requirements.

- For example, the Minnesota and Colorado green banks received $20 and $40 million capital infusions from their state legislatures respectively; see https://mn.gov/commerce/energy/consumer/energy-programs/climate-innovation.jsp and https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb21-230.

- There is a proposed mechanism to apply for exemptions from the domestic content requirements if meeting the criteria would increase overall project costs by 25% or more or if satisfactory domestic options are not available. However, to date no guidance has been released on how this exemption would work in practice. For more information, see https://www.lawyersforgoodgovernment.org/faq-page-elective-pay.

- For more information see Lawyers for Good Government’s guidance brief on bonus incentives, including direct pay, at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rIUeVxha7u5OK-NsNAZz6M3bi__Qc1oT/view.

- See Proposed Regulations § 1.48-13(d) for more information.

- For more information, see Lawyers for Good Government’s FAQ on Elective Pay at https://www.lawyersforgoodgovernment.org/faq-page-elective-pay.

- Owners should be conscious of consumer data privacy laws when designing and deploying these software tools.

- Bridge loans cover or “bridge” the period between the outlays for a project and the collection of the ITC via direct pay.

- CDE certification is related to but distinct from CDFI certification. Both are administered by the CDFI Fund.

- While most banks have comfortably passed their CRA requirements in recent years, with just 1.5% of banks receiving a failing grade from 2018–2022, a recently proposed update could make compliance more challenging. The new rules make it so banks will automatically get credit for community development loans and investments made outside of branch networks as long as they meet the relevant criteria, which could simplify the process of using CRA funds to stand up national or regional efforts. These programs could also be tailored to allow commercial investments to meet several of the 12 impact and responsiveness factors identified in the new rules, which could enhance banks’ ability to meet their requirements and make these investments more compelling. However, there is currently a preliminary injunction on adoption of the new CRA rules. While this program could warrant CRA investment under either the old or new criteria, entities may wish to wait until there is greater clarity in the market before undertaking the complexity of approaching commercial banks for CRA-eligible investments.

Contributors & Special Thanks

Contributors: Jillian Blanchard, Lawyers for Good Government; Franz Hochstrasser, Lawyers for Good Government; Yuning Liu, RMI; Whitney Mann, RMI; Russell Mendell, RMI; A.C. Meyer, Lawyers for Good Government; Vincent Nolette, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law; Andy Posner, Capital Good Fund; David Posner, RMI; Amy Turner, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law; Uday Varadarajan, RMI.

Additional thanks: Kevin Boes, Broadstreet Impact; Maria Castillo, RMI; Meredith Cowart, RMI; Eric Hangen, Squared Community Development Consulting; Jubing Ge, RMI; Janelle Gendrano, Climate Access Fund; Kevin Hill, NCRC; Roger Horowitz, Solar United Neighbors; Sam Mardell, RMI; Zach McGuire, Columbus Region Green Fund; Jesse McKinnell, CEI Maine; Julia Meisel, RMI; Alisa Petersen, RMI; Jingyi Tang, RMI.