A parking lot with charging stations for electric cars.

Four Actions to Take EVs into the Mass Adoption Phase

The global shift to EVs has reached a potential tipping point. Here’s how to push cleaner driving forward.

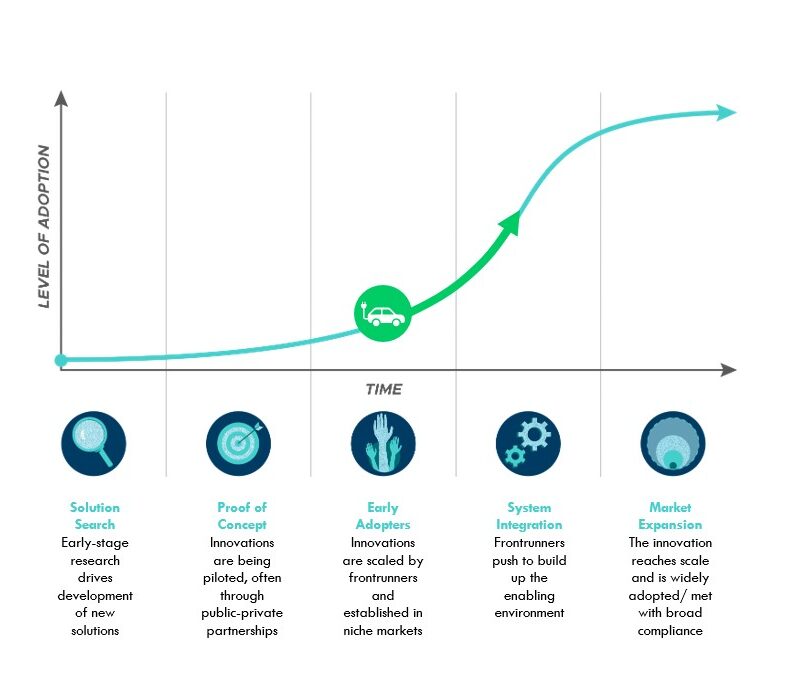

A new report from the UK-based nonprofit organization Centre for Net Zero, to which RMI contributed, considers the next phase of the global electric vehicle (EV) transition: mass adoption. This phase comes after years of targeted policy support, falling battery costs, and expanding global supply chains. It represents the steep part of the “S-curve” of technology adoption and is characterized by rapid cost reductions, improvements in quality, and stiffening competition.

Exhibit 1. EVs on the Technology S-Curve

Source: RMI, Harnessing the Power of S-curves

This step involves overcoming challenges and embracing the opportunities that come with a rapidly scaling industry as well as the requirements for infrastructure integration. Three clear goals stand out: ensuring the transition is rapid, that it is equitable, and that it is systemically integrated with clean energy networks.

EV policy today, and what comes next

One in five new cars sold worldwide is already electric, and even though the US market is facing headwinds, global sales are continuing to accelerate rapidly. But this momentum is not enough to secure a cleaner transportation future. As with the rise of the internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle, which was supported by massive investment in roads, highways, and shifting city planning and zoning policies, today’s transition is driven by policy and technology. Without decisive policy, investment, and coordination, feedback loops could slow or reverse, lock in fossil fuel dependency for longer, or result in the build-out of supply chain, energy, and other infrastructure that is either too slow or not fit-for-purpose. Policy consistency is key to boosting market competitiveness and encouraging consumer confidence.

This article highlights four actions that can form the basis for a new strategy for the next phase of rapid growth:

- Close the purchase price gap

- Expand access to affordable charging

- Prepare the electricity grid

- Invest in circular and efficient manufacturing

-

Close the purchase price gap

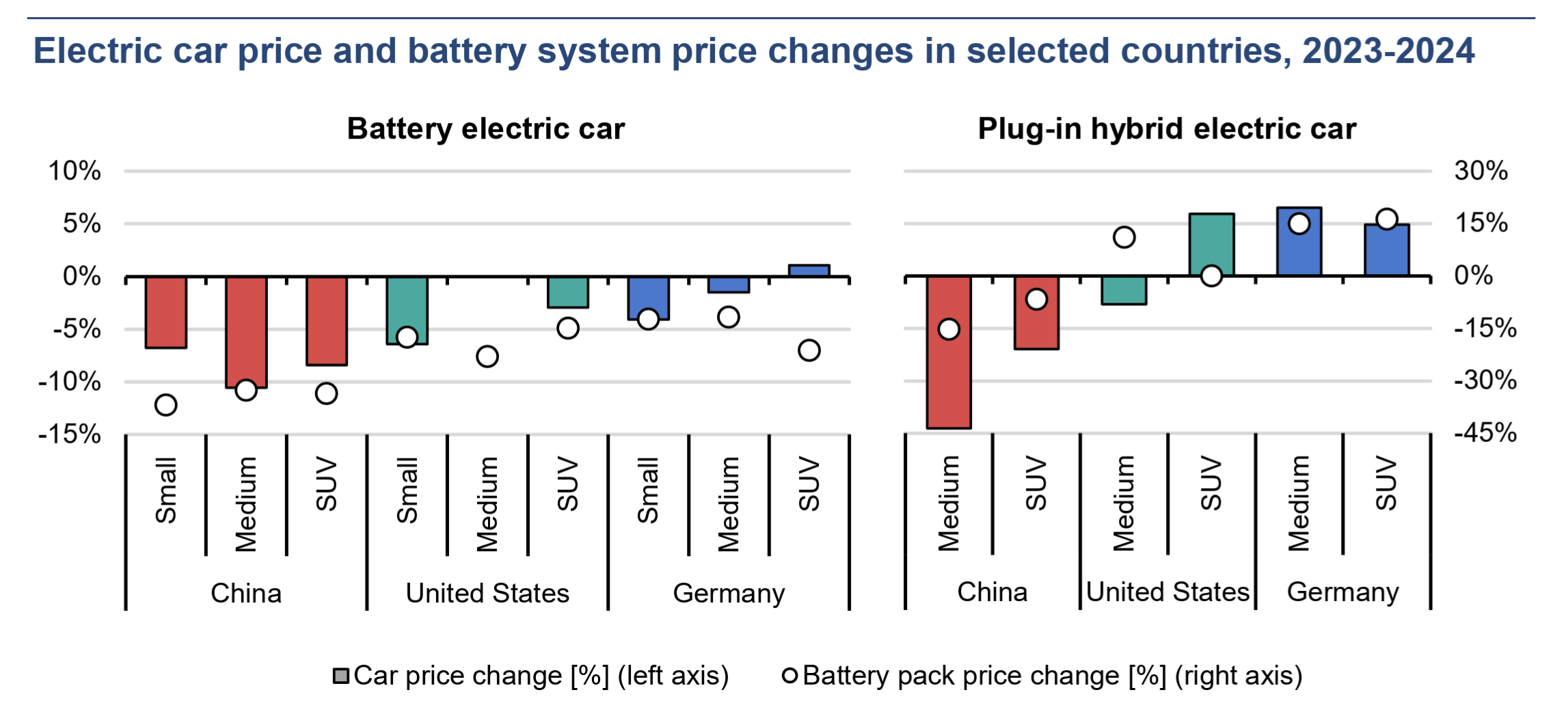

In terms of new vehicles, EVs offer lower running costs than ICE vehicles, but this advantage is partially offset by higher upfront costs. 2024 saw global battery pack prices fall by 20 percent even as average size increased, but this hasn’t fully translated to lower retail prices for consumers. In China, a 30 percent fall in battery prices translated into a 10 percent decline in electric SUV prices; in Germany, EV retail prices rose slightly despite a 20 percent battery cost drop.

We expect costs to continue falling due to fundamental dynamics such as technological learning and economies, but subsidies and tax incentives can also play a role in closing the gap sooner. Policymakers will increasingly need to consider more targeted support for those who need it most. Examples of innovative financing models that can broaden access include blended finance models, ‘pay-as-you-drive’ schemes, flexible leasing, green bonds and concessional loans, and battery-as-a-service offerings.

Exhibit 2. Falling prices for electric car battery systems, 2023–2024

Source: IEA (2025) Global EV Outlook 2025

-

Expand access to affordable charging

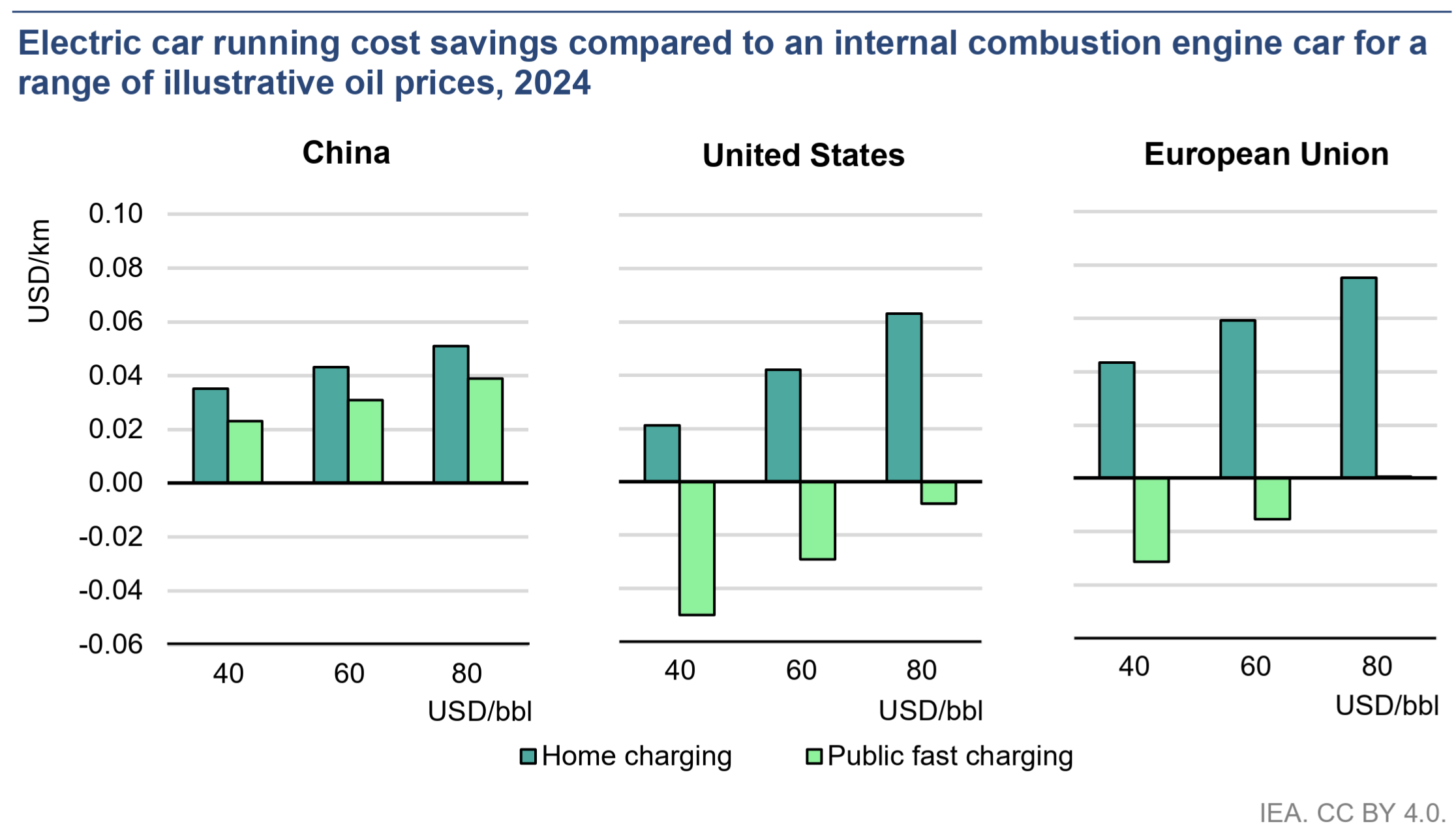

Without a reliable, accessible, and affordable public charging network, EVs cannot scale. Public charging is consistently cited as a key barrier, particularly among marginal adopters who prioritize convenience, accessibility, and range confidence. Survey data confirms that purchase intent rises sharply when public charging is perceived to match the ease of refueling an ICE vehicle.

Public charging is significantly more expensive than home charging — up to 10 times so in some countries. Yet, as EVs go mainstream, those dependent on the public charging network will form a growing share of users. For example, in Los Angeles, analysis by NREL finds that, by 2035, public charging could cost an additional $300/year for the 20 percent of households who will lack at-home charging access. Parallel efforts on expanding access to home charging and increasing the affordability of public charging are needed.

Smart public charging — matching demand with cheaper electricity supply — can also help close the affordability gap by delivering cheap off-peak charging to households, as it does in domestic settings.

Centre for Net Zero’s research shows that dynamic pricing can encourage drivers charging outside of their homes to do so when electricity costs are cheaper, reducing EV running costs below those of petrol cars. Lower-income areas showed the strongest behavioral response, indicating that they may stand to gain the most.

Exhibit 3. EV home and public charging cost savings compared to ICE for a range of illustrative oil prices, 2024

Source: IEA (2025) Global EV Outlook 2025

-

Prepare the electricity grid

The need to expand and reinforce grid capacity is well understood. But simply building up the grid is not enough. Existing approaches to utility planning are creating bottlenecks for charging infrastructure expansion. A modern, EV-ready connection regime must prioritize speed, transparency, and flexibility for vehicles of all sizes.

On the supply side:

Current regulatory models, based on cost prudence and recovery, often cause investment timelines for grid upgrades to be mismatched with the needs of EV charging installations. While EV charging sites can usually be built in less than six months, distribution system upgrades can take two to five years.

Better forecasting, guided by tools such as RMI’s GridUp, can help grid planning shift from reactive to proactive. Anticipatory investment in grid upgrades, reforms to connection processes, and increased utilization of grid flexibility are all solutions that can help the grid better meet EV charging demand.

Flexible service connections can allow charging sites to make more efficient use of existing grid infrastructure. By working with the capacity that is typically available outside of a few peak hours of the year, these alternatives can power charging a majority of the time without creating a need for more investment in the grid. This allows charging to become available faster at less cost to the utility.

On the demand side:

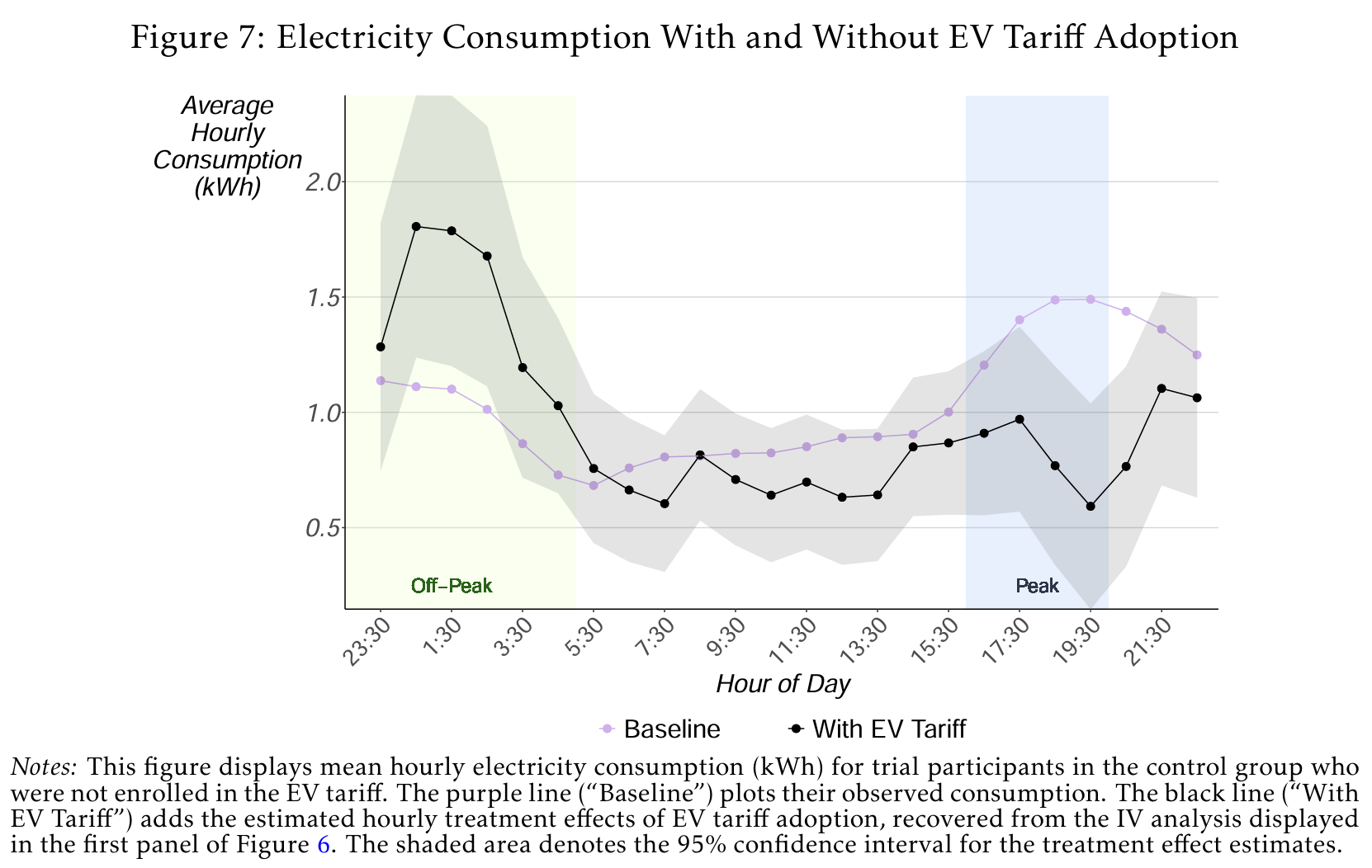

If left unmanaged, widespread charging will exacerbate existing grid constraints, leading to instability, rising infrastructure costs, and higher bills for consumers.

Managed charging will be a key solution. RMI analysis shows that managed charging could reduce EV charging contribution to peak demand by nearly a third in New York State. EVs could also absorb surplus renewable energy and ease congestion, ultimately lowering system costs. Similarly, Centre for Net Zero analysis shows managed charging at home can shift the entirety of EV demand to low-cost, low-emission off-peak periods. Where dynamic pricing exists, these cost savings can be passed through to consumers — around £650 for UK customers compared to flat-rate tariffs.

Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) technology — which allows consumers to export electricity back to the grid from their EVs — could provide even more of the same system benefits but will require bi-directional capability. In the UK, Center for Net Zero finds that widespread V2G adoption could absorb larger volumes of variable renewable generation, leading to a reduction in average wholesale electricity prices of up to 10 percent by 2030.

Exhibit 4. UK trial showing electricity demand with and without managed charging

Source: Centre for Net Zero (2025), AI in Charge: Large-Scale Experimental Evidence on EV Charging Demand

-

Invest in circular and efficient manufacturing

EVs already have a structural advantage over ICE vehicles: while both require material inputs, EVs rely on a one-time extraction of battery minerals, whereas ICE vehicles lock in a perpetual dependence on fossil extraction.

Nonetheless, the rising demand for critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel raises legitimate sustainability concerns. One answer is battery recycling, which is already advancing rapidly: In 2019, 59 percent of lithium-ion batteries were recycled globally, and estimates now suggest this figure could be approaching 90 percent. Modern processes can recover from 80 to 95 percent of minerals, and this is expected to rise to 95–99 percent within a decade. Announced recycling capacity is already sufficient to manage all end-of-life batteries through 2030.

Exhibit 5. Total battery mineral ore needed to sustain EVs vs. oil extracted each year for non-electric vehicles

Source: RMI

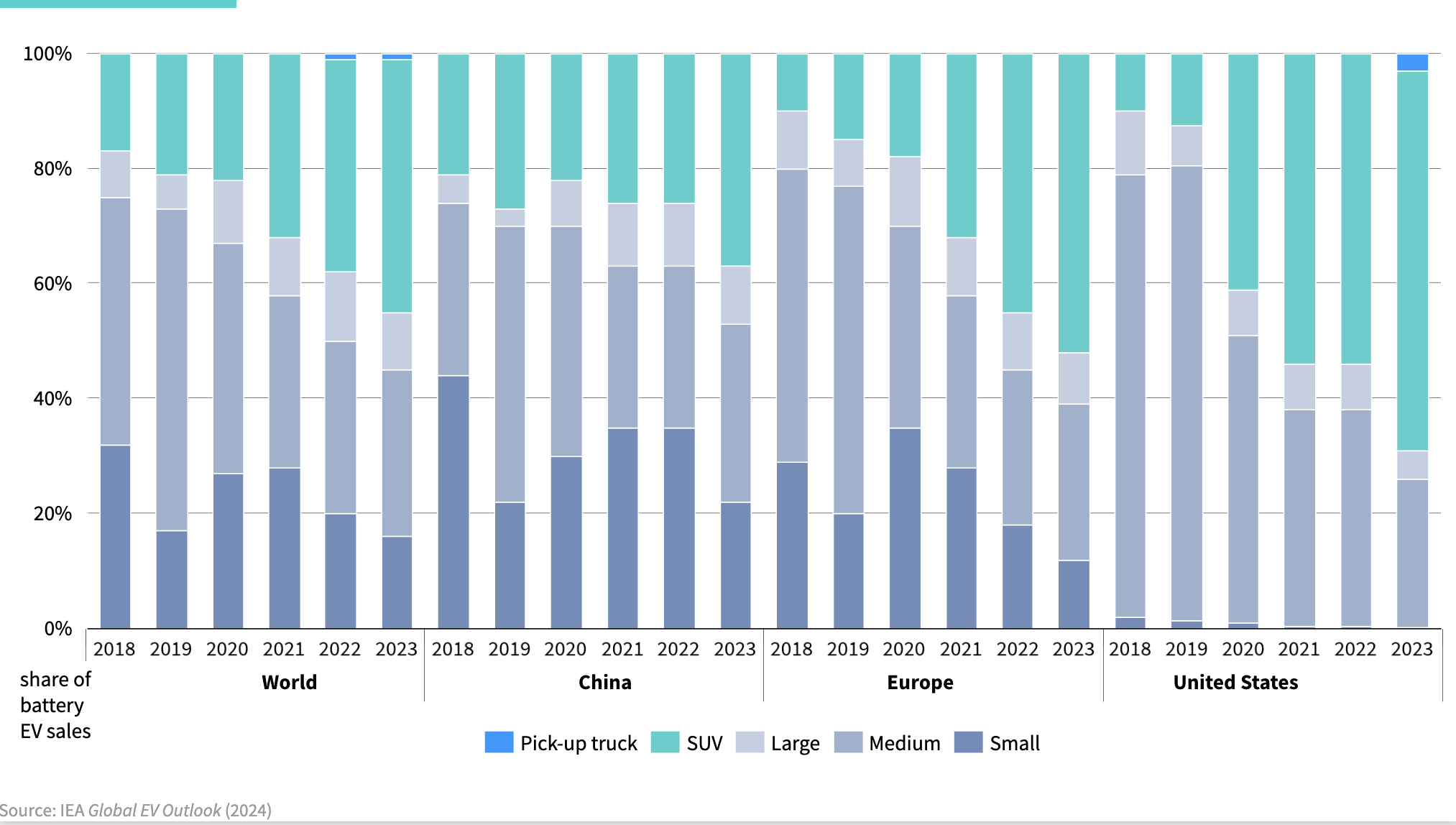

The need for critical minerals, and even new battery recycling capacity, can also be reduced by improving vehicle efficiency. This can be achieved in several ways, including improved aerodynamics, the use of lighter materials, and vehicle size. Smaller EVs require smaller batteries — which have the added benefit of lower costs. For example, the already heavyweight GMC Hummer EV requires a 246 kWh battery that weighs as much as a sedan itself, while the compact Chevrolet Bolt EV only needs a 66 kWh battery. Unfortunately, efficiency is not always top of consumer minds: demand for ever bigger cars continues to rise.

Exhibit 6. Share of EV sales by car size, 2018-2023

Source: RMI (2024), The Battery Mineral Loop

The goal is no longer simply more EVs, but smarter, fairer, and more sustainable deployment — ensuring that EVs work with, not against, the systems they depend on. The four actions above are not comprehensive but represent the priority areas where stakeholders should seek to align as EVs enter this critical next stage. Getting this right will make the difference for a healthy environment, stronger economy, and a sustainably sourced future for cars.

The full report is available from Centre for Net Zero at the following link:

Scaling the S-Curve: The Exponential Phase of EV Adoption.